HISTORY

Mackinac Island Carriage Tours is the world’s oldest Horse and Buggy Service with approximately 100 carriages pulled by over 400 horses.

Carriage men officially began providing tours of the Island in 1869 when the first city carriage license was issued. In 1948, the carriage men officially established Mackinac Island Carriage Tours, Inc.

The founders of Mackinac Island Carriage Tours have had a very prominent role in making Mackinac Island Michigan’s most popular tourist attraction. It was the carriage men, led by their president, Thomas Chambers, that petitioned the Village of Mackinac Island to ban the automobile as the “horseless carriage” startled the horses.

Descendants of the founding carriage men still actively manage the company that was formed over 100 years ago.

Today, Mackinac Island Carriage Tours, Inc. is the world’s largest, oldest and continually operated horse and buggy livery, with approximately 100 freight and passenger carriages put in motion by over 400 horses.

Mackinac’s Horsemen

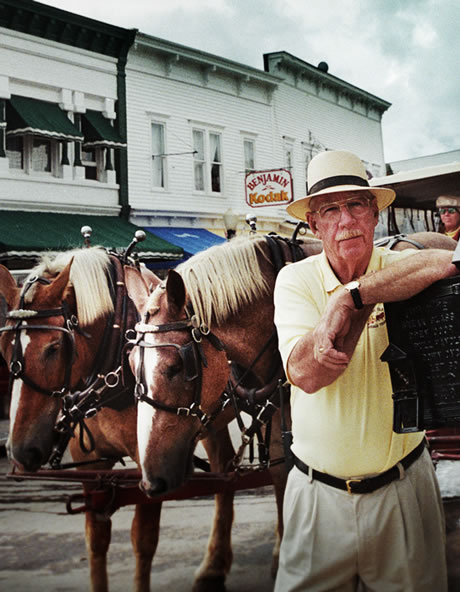

ON A MISTY summer day, Chambers picks me up at my inn in his dark-green, cream-trimmed carriage. Bill’s oldest brother, Bud, built the carriage in 1950, patterning it after a mid~8th-century Brewster carriage. The trademark gun-metal green of such carriages gave rise to the term “Brewster green.” At the reins is Dr. Bill’s old friend Buck Sharrow, a seasoned coachmen. As we’re introduced, Sharrow Looks down at me from his perch. His beefy face, set off by a sharp nose, spreads into a shy smile.

As we take off in the carriage, Dr. Bill talks about putting his veterinary training to work on Carriage Tour horses, the official side of his vet business. The unofficial side is the middle-of-the-night emergency calls he’s answered over the years for other island horses. It’s a practice he would like to avoid, but as he says, “What are you gonna do?”

The obvious comparison to Chambers is the English author/country vet James Herriot. But that would be to misconstrue Dr. Bill’s humor. It’s all Irish.

As the carriage moves with a steady grace past the stately mansions that line Huron Street, Dr. Bill recounts his family’s island history. He tells it as if it happened yesterday, with pithy asides. It’s a blue-blood island history he could well boast about, but instead he says, “Yeah, that and $2.50’ll buy a pack of Kents.” Nearly every ethnic group ever to make contact with Mackinac Island flows in the Chambers’ veins. “But we only admit to the Irish,” Dr. Bill adds with a hearty laugh.

The Chambers’ genealogical lines lead back to carriages. Dr. Bill’s great-grandfather Tom Chambers was driven out of Ireland by the potato famine. He settled on Mackinac Island in 1830, and later built a frame house and stable at the corner of Market Street and Cadotte Avenue.

There, he raised a family, broke and trained his fine hackney horses and built carriages. Tom’s son and grandson, Dr. Bill’s father, were all carriagemen.

Dr. Bill’s great-grandfather, E.A. Franks, was proprietor of the island’s Mission Hotel during the mid-18th century and a carriageman. Franks wasn’t Irish, but he had a good dose of characteristic carriageman spunk. As proof, Dr. Bill likes to tell an anecdote recorded in the city minutes in 1868. “Franks and Cable both obtained licenses to operate a horse-drawn carriage,” he says. “Then there’s a little note attached that reads: ‘Cable paid for his.’ ” The insinuation here, according to Dr. Bill, is that Franks, like most carriagemen then, didn’t believe in licenses and wouldn’t pay for his.

That free spirit reared its head again in 1896 after the first automobiles made their noisy entrances onto the island. The carriagemen got together and asked the Mackinac Village Council to ban the “dangerous horseless carriages.” Dr. Bill’s great grandfather and great-great-uncle signed the petition.

The village council voted to forbid automobiles and the Mackinac Island State Park Commission supported the ban. Relations between the carriagemen and the park commission weren’t always so smooth. Around the same time, the Corrigan who signed the request to ban autos (another ancestor of Dr. Bill’s) was fined for driving his carriage in the park without a license.

Corrigan fought it all the way to the Michigan Supreme Court. His appeal was denied, but on the local level he demonstrated once again that carriagemen were a group to be reckoned with.

By this time, Mackinac Island had evolved into a wealthy resort community, driving the demand for carriages. The carriagemen responded to the bonanza by crowding their carriages along Main Street–up to 80 at a time–to greet passengers coming off the boats. Competition was fierce, price cutting common, brawls occasional.

In 1924 the Mackinac Island State Park Commission stepped in to mediate, calling a meeting of carriage owners. The result was the Carriagemen’s Association, a loosely connected group whose self-elected governing body set fare prices.

Two decades later, liability insurance and the cost of running a stable pushed the carriagemen toward a closer union. In 1947 each carriageman who could provide a team of horses and a carriage was issued shares of stock in a new corporation: Mackinac Island Carriage Tours Inc.

The new organization didn’t change life much for a young Bill Chambers, 15 that year, or for his brothers and sister, Sally. Life rolled on at its familiar, pleasant pace.

The Chambers children, like their father and grandfather before them, were born in the house on Market and Cadotte. They grew up with the proud hackman tradition and a mother, Sam (nee Frank, but 50 percent Gallagher, Bill is careful to add), who kept them well fed with stories of their Mackinac heritage.

Illustrating her stories were old photographs like the one hanging in the lobby of the island’s prestigious Grand Hotel. It’s of Mrs. Potter Palmer (of Chicago’s Palmer House hotel), seated in a fancy carriage around the turn of the century. The carriageman standing with the team is Dr. Bill’s grandfather, William Chambers. “If you look very closely at that picture, you can see the Chambers family insignia on the harness,” says Dr. Bill.

Virtually everything the boys did from the time they could walk trained them to be horsemen. As toddlers they napped in carriages. “Anytime we’d get fussy my mom would say to my dad, ‘Here, take this kid,’ ” Dr. Bill says. “To this day, I still get a little groggy in a carriage.”

The children got so accustomed to the gentle horse-and-buggy rhythm that, as Dr. Bill recalls, “The first time they put us all in a car, we all spit up.”

The boys were never too young to go in the stables. “As soon as we were toddling around we played in the barn,” Dr. Bill says. “But first, my father walked through and picked out certain horses and said, ‘You can walk by that one and that one, but not that one.’ ” The boys obeyed because, as Dr. Bill puts it, “You knew you’d get your head kicked off if you didn’t.”

Carriage-driving lessons began for the preschoolers on their dad’s lap. “At first, we’d hold the back of his hands,” Dr. Bill says. “Then, when we were ready, he’d let us hold the reins.”

By the time they were teenagers, the boys were working with their father and grandfather as footmen to the wealthy-families with household names like Mennen, Swift and Hoag (of Hannah-Hoag whiskey). Occasionally, the boys were invited to parties at the mansions in the island’s prestigious East and West Bluff neighborhoods. They were allowed to go, but not without their dad and granddad’s counsel: “Don’t get too uppity. Coachmen use the back door,” Dr. Bill recalls. “Remember that.” Those barriers between the wealthy summer people and the carriagemen, Dr. Bill is quick to point out, have broken down over the years.

After high school, Dr. Bill left the island to attend vet school at Michigan State University. He served in the Army Veterinary Corps in the Korean war and afterward settled in Minneapolis. Of his off-island period he says only, “I survived it.”

When his dad died in 1972, Dr. Bill returned to the island to help his brothers with the carriage business.

SHARROW, OUR COACHMAN, drives into the yard at Market and Cadotte, where little has changed in 170 years. At the side of the yard sits the white clapboard home Tom Chambers built in 1830. White ruffled curtains hang in the windows, a couple of ancient lilac trees adorn the yard and a tangle of colorful flowers sprout around the foundation. Bill’s sister, Sally, lives here now. Sara Chambers, Bill’s mother, lived here until two years ago, when–alert and lively until her last days–she died at age 97.

In the yard between the house and stables, Bill breaks all the colts that will become Carriage Tours horses–a task he takes seriously. “Every move you make on a colt makes an impression on them,” he says. “When they’re born, even before their mother licks ’em off, we put our fingers in their ears, nose, mouth. That way they won’t mind being bridled later. Everything matters with a colt–how you feed ’em, the way you turn in the stall.” Nowadays, Tom Chambers’ green-trimmed stable is where Bud Chambers builds and repairs carriages for Mackinac Island Carriage Tours. As private as Bill is gregarious, Bud is happiest left alone to build his carriages.

Unlike Bill, Bud has never moved off the island. He’s never moved farther from the house on Market and Cadotte, in fact, than a few blocks away–across the Grand Hotel’s golf course, as the crow flies. “We like to say that the farthest he’s ever gone is from the eighth hole to the 15th,” Bill says with a chuckle.

With the exception of the 35-person Carriage Tours taxis that transport guests through the state park, Bud has built every carriage the company uses. He does it using almost the same tools and procedures Tom Chambers did.

One major difference in carriage design was born out of the way the business has changed in the last 50 years or so. Just after World War II, for instance, when the island’s tourism business sprouted, the company found it needed to make bigger carriages. Bud already was helping his father by that time, so he helped design bigger taxis. He sliced old carriages through the middle, added a section and reassembled them. The results are the red-and-yellow 16-person taxis that ply the streets of Mackinac today.

For the most part, Bud’s everyday tools are what most people consider family heirlooms. Bill points to a wrought-iron device set against the front wall. Made by B.E Goodrich, the machine is used to tighten the rubber around carriage wheels. “My grandfather bought it in 1885,” says Bill. “We still use it every day.”

If a tool wears out, Bud makes a new one. “That’s what it means to be a carriageman,” Bill explains. “You have to shoe your own horses, fix the harness, train and drive your horses, make your own carriage.

“We operate a system of transportation that was defunct in 1900; everything is specialty,” he continues, looking out the door to where Sharrow waits atop the carriage.

“Like, there’s only one of Buck Sharrow. All the rest are in St. Anne’s Cemetery.”

FROM THE CHAMBERS homestead, Sharrow negotiates the carriage up the hill past the Grand Hotel. As we talk, Dr. Bill leans forward every now and then to include Sharrow in a joke. The coachman looks back politely but quickly, careful to keep his eyes on the team.

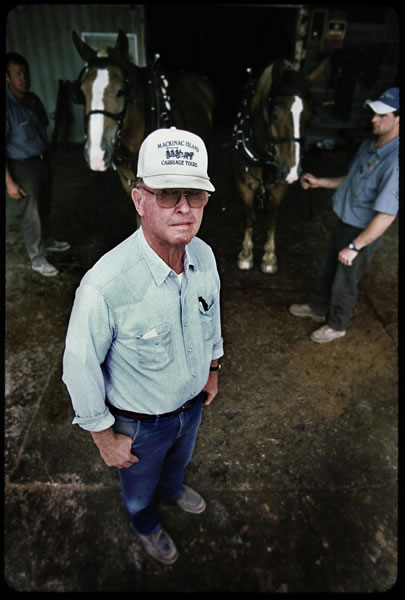

As the carriage shop is Bud’s world, the Carriage Tours’ stables and barns at the top of Cadotte Avenue is the domain of Dr. Bill’s brother Jim. He is head nanny to the company’s 350 horses. As we’re introduced, his charges–the ones that aren’t working–are frisking around in a pasture behind the barns.

The company’s horses consist mostly of hackneys, tawny-colored high-spirited driving horses. Carriage Tours is one of only about 15 hackney horse breeders in North America. The rest of the herd is made up of Percherons, the 2,000-pound gentle giants the company uses to pull the big green taxis.

Six months a year, Jim supervises the endless feeding, brushing, washing, harnessing and unharnessing of the horses. At season’s end, he ships them by ferry to the Upper Peninsula. There, the horses spend the winter feasting on 900 tons of hay, 4,000 bushels of grain and 120 tons of high-energy pellets called Master Mix, a feed Dr. Bill helped develop for horses that winter in severe climates.

For years, Jim spent the off-season in Upper Peninsula with the horses. Nowadays, he flies back and forth. “Then once the ice makes,” Dr. Bill explains, “he snowmobiles over and back every day.” Caring for the horses has grown as island tourism has ballooned in the last two decades. “We move so many more people than in my dad’s time,” Dr. Bill says. “He’d roll over in his grave if he saw what we do now.”

The work is hard and profit margins slim. ‘”This business has nothing to do with money. You’d better love it,” Bill continues. “We don’t punch in at eight and leave at five. This is labor-intensive. You have to maintain the herd. You could never replace these horses that are trained just to work on Mackinac Island. It took years to assemble this herd. We spend a lot of time weeding out the old ones and making sure the new ones can function safely.

“There are many people who don’t understand how fragile the horse business is. They take it for granted. Our tour and freight/dray rates are moderate compared to what would happen if you didn’t have six generations of experience.”

Indeed, as much as the island’s horse lifestyle is heralded, its strong footing in island life is constantly in danger of being eroded. That keeps the brothers busy in politics to make sure horse-and-carriage interests are protected. “We try to keep a presence, but that’s harder and harder to do,” says Bill. “The population is changing. “

That change is from venerable island families who no longer want to keep their own liveries and newcomers who don’t want the expense. Without their own horses, island dwellers have three options to get around: by foot, bicycle or taxi. So residents have pushed to allow golf carts. The thought makes Dr. Bill shudder. “We know horse-drawn transportation is slower,” he says. “We know you’re apt to miss the boat occasionally. But I say, ‘Take a deep breath and relax. You’ll live a lot longer.’ We’re not Disneyland.

“But there always have been threats,” he adds. “Unless we have committed people who aren’t interested in the buck this business won’t make it–thank God some of our children have that commitment. We have to train our own people and give them something to pass on.” He pauses, then reflects: “But my biggest fear is not being able to make a commitment to these people.”

And the fifth generation is counting on that commitment. Dr. Bill’s son Brad is the corporation’s treasurer. His other son, Jeff, is a cardiologist in Minneapolis. It’s anybody’s bet how long he’ll be able to stay away from the island and the family business. “He calls every day to check on things,” says his father.